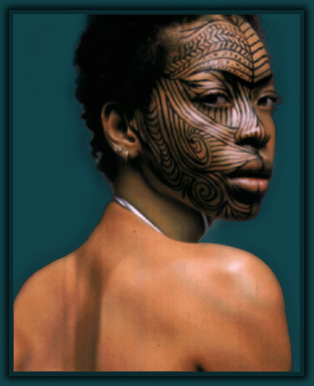

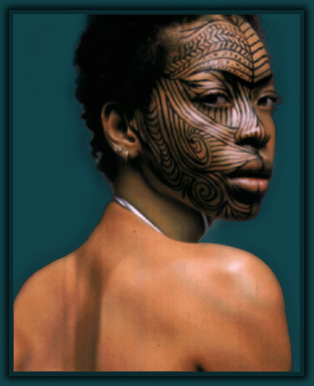

Erykah Badu

In his 1966 essay/poem, "The Changing Same (R&B and New Black Music)," LeRoi Jones wrote that "the emotion is the devotion." Assumin' that still holds true, speaking on how a piece of music grips and steers ancestrally informed hips can make for completely valid critique. This spiritual perspective ain't just valid, Jones meant, but revolutionary. To paraphrase: When James Brown screams and Pharoah Sanders says "Ommmm," these moments are more radical than sit-ins. "We need to get Feel-ins," Jones wrote, "Know-ins. Be-ins."

In his 1966 essay/poem, "The Changing Same (R&B and New Black Music)," LeRoi Jones wrote that "the emotion is the devotion." Assumin' that still holds true, speaking on how a piece of music grips and steers ancestrally informed hips can make for completely valid critique. This spiritual perspective ain't just valid, Jones meant, but revolutionary. To paraphrase: When James Brown screams and Pharoah Sanders says "Ommmm," these moments are more radical than sit-ins. "We need to get Feel-ins," Jones wrote, "Know-ins. Be-ins."

Maybe this is what Erykah Badu means by Baduizm: this organic joining of music, movement, and the resultant heightening of consciousness. Baduizm is rooted in an old vocab, one shook on sidewalks ("Ooh, shaaake it to the East / Shaaake it to the West"); resisted and surrendered to in chu'ch; remembered by that favorite old-school aunt who kept a jar of Jack in one hand, a Benson & Hedges in the other. Baduizm serves as a conduit for an awakening of something dark, familiar, and long slept.

But not dead. Come on, y'all: Although her timbre and phrasing be evocative, Erykah Badu ain't the Second Coming of Billie Holiday; just like D'Angelo-with whom Badu shared a worthy remake of Marvin Gaye and Tammi Terrell's "Your Precious Love" on the High School High soundtrack-ain't Gaye revisited. See, just 'cause elders aren't among us doesn't mean they've stopped teaching. And their young progenies, who simply practice what was preached, should not be cast in the shadows of death.

Yea, though, she walks. Just like those determined, searching blues wimmin 'fore her, Dallas-bred Badu, 26, left "normalcy" (in her case, Grambling State University) in search of song, movement (she's a trained dancer), and a certain, complicated truth of her own. Changed her last name too so it'd be her scat. Little wonder why, in the video for her Five Percent Nation-inspired first single, "On & On," Badu's character-an intimate mix of The Color Purple's Shug Avery and Miss Celie-uses these pursuits to carry her home, 'umph-a-sized by the truth: "If we were made in His image then call us by our names / Most intellects do not believe in God but they fear us just the same." Later, she will defiantly slur: "Goddammit, I'ma sing my song."

Which is exactly the point-this laying claim, embracing of self. Baduizm represents a progression in sound and creativity, although Badu does have a Mary Moment (as in Ms. J. Blige) on her remake of Atlantic Starr's 1983 "Touch a Four Leaf Clover," produced by Ike Lee III (Michael Jackson and Toni Braxton). It's hard not to. Any female singer merging old-school R&B with hip hop up-funk wanders into Blige's dusky waters. (Hell, especially if it's a remake). Blige isn't the polished singer that Badu is, but on this turf, Blige is generally more powerful and dramatic.

Which is exactly the point-this laying claim, embracing of self. Baduizm represents a progression in sound and creativity, although Badu does have a Mary Moment (as in Ms. J. Blige) on her remake of Atlantic Starr's 1983 "Touch a Four Leaf Clover," produced by Ike Lee III (Michael Jackson and Toni Braxton). It's hard not to. Any female singer merging old-school R&B with hip hop up-funk wanders into Blige's dusky waters. (Hell, especially if it's a remake). Blige isn't the polished singer that Badu is, but on this turf, Blige is generally more powerful and dramatic.

But Baduizm travels further and leaps eras. Badu, who wrote all but "Four Leaf Clover," reaches for the joyful, exacting vocal arrangements of the Sweet Inspirations and the Emotions; the complexity of Sarah Vaughn and Minnie Riperton; the soaring production ö la Gamble and Huff or Earth, Wind & Fire's Maurice White; the backbone of Willie Mitchell. The onomatopoetic, all-net "Rim Shot" is Baduizm's conceptual Alpha and Omega, a rhythmic homage to the emancipating drum, requisite in African dance and ritual. Her near-trademark, '40s- and '50s-ish "Ooo-wee, ooo-wee-ooo"s are laced throughout, especially on the empowering "Appletree" ("See, I picks m'friends like I picks m'fruit / My Ganny told me that when I was only a youth"). Badu's blues recognition comes courtesy of "Afro" (inspired by Amir from the Roots), in which she launches a low Levee moan before, briefly erupting into laughter, she directs: "You need to pick yo' Afro, daddy / Because it's flat on one side."

Amazin' what a little Afrosheen can do when applied directly, as on the contemplative, Roots-produced "Other Side of the Game," possibly Baduizm's finest track. Dedicated to political prisoner Mumia Abu-Jamal, "Other Side" is the voice of a pregnant sister struggling to stand by her man despite his perilous "complex occupation." Elder Gaye's lessons-his trademark vocal layering, echoes, drums, yearning, prayers-are most practiced here, and a quiet strength resonates: "Now I ain't sayin' that this life don't work / But it's me and baby that he hurts / Because I tell him right, he thinks I'm wrong / But I love him strong." Her final words? "Peace after revolution," she cries. Then, gravely, she reminds: "But we paid, though."

Erykah Badu comes from a place where, by virtue of a scooped, lifted tongue, "there" is pronounced "thur"; she is indeed a Su'thun Girl. For her, "well" (on "Sometimes (Mix #9)") comes out a Reverend-rendered, bottom-lined "waail." Only she could gently call you "baby," "honey," and finally "pat'nah" in one song (the snaking, seductive "Certainly," where Badu soft-breathes trumpet bops). According to her mood (and perhaps which direction the wind is blowing the smoke of her meditative incense stick), words are either exorcised out her mouth or gently persuaded. That's Baduizm. And we hear you, m'dear.

Return to Shazzar's page!

In his 1966 essay/poem, "The Changing Same (R&B and New Black Music)," LeRoi Jones wrote that "the emotion is the devotion." Assumin' that still holds true, speaking on how a piece of music grips and steers ancestrally informed hips can make for completely valid critique. This spiritual perspective ain't just valid, Jones meant, but revolutionary. To paraphrase: When James Brown screams and Pharoah Sanders says "Ommmm," these moments are more radical than sit-ins. "We need to get Feel-ins," Jones wrote, "Know-ins. Be-ins."

In his 1966 essay/poem, "The Changing Same (R&B and New Black Music)," LeRoi Jones wrote that "the emotion is the devotion." Assumin' that still holds true, speaking on how a piece of music grips and steers ancestrally informed hips can make for completely valid critique. This spiritual perspective ain't just valid, Jones meant, but revolutionary. To paraphrase: When James Brown screams and Pharoah Sanders says "Ommmm," these moments are more radical than sit-ins. "We need to get Feel-ins," Jones wrote, "Know-ins. Be-ins."